Personal Minimums

Everyone has, or should have, personal minimums. My personal minimum for fuel is that I want to be on the ground with 10 gallons on board. The second part of that is I want those 10 gallons in one tank. During my 950 hours in our Mooney, I have only violated that rule once. Last year, on a very long flight during the daytime, I landed with 8 gallons on board. At 9.1 gph, that’s about 50 minutes of flight time, which exceeded the daytime FAA VFR minimums of 45 minutes. However, I didn’t feel great about it because it didn’t meet the “Richard Brown 10 gallons personal minimum.”

In addition to personal minimums, we all have different procedures that we are comfortable with and ones that we are not. The topic of running a tank dry generates strong opinions on both sides. I’m not here to say what others should or shouldn’t do, but I am going to share what I do, why I do it, and my experience with running tanks dry.

I fly a 1965 Mooney M20D, converted to retractable gear and constant speed prop, essentially making it an M20C. It has a Lycoming O-360-A1D 180 hp carbureted engine. Keep in mind that an injected engine will behave a little differently when the fuel stops flowing, and if you have a turbo and are up high, the restart is very different.

Pilot Operating Handbook Procedure

The 1974 M20C POH recommends, “After takeoff with both tanks full, use fuel from one tank for one hour; then, switch to the other tank and note the time. Use all the fuel from the second tank. The remaining fuel endurance in the first tank can be calculated from the time it took to deplete the second tank, less than one hour.”

This procedure was published by Mooney to provide a way to know your remaining fuel on board. It was written in the days of inaccurate gages, no fuel flow metering or totalizers.

Now, with CiES digital fuel senders and a JPI EDM900 engine monitor, I know down to about a tenth of a gallon, the amount of fuel I have remaining. Therefore, I don’t follow the POH recommended procedure to know my remaining fuel. I follow it to get maximum range and have all my remaining fuel in one tank when landing.

Now, with CiES digital fuel senders and a JPI EDM900 engine monitor, I know down to about a tenth of a gallon, the amount of fuel I have remaining. Therefore, I don’t follow the POH recommended procedure to know my remaining fuel. I follow it to get maximum range and have all my remaining fuel in one tank when landing.

I have some friends that switch tanks every 30 minutes, some who switch every hour, and other variations. The length of the flight determines my tank switching procedure. If it’s a short flight and I can take off and land on the same tank with 10 gallons remaining, I won’t even switch tanks. If it’s a longer flight, maybe 2 to 2 ½ hours, I’ll fly the first hour on one tank and switch over to the other tank for the remainder of the flight. That is because I will still have 10+ in the tank I am landing on. I think you get the idea.

What Happens When You Run Out of Fuel

I have a good friend who has an M20C and is preparing to go on a trip from California, essentially flying around the whole country. She’s had her plane for a few years, and I’ve talked to her about running a tank dry and what it is like. But hearing about it and doing it or seeing it done, are very different things. I took her up for a short flight to show her what happens.

A couple of days prior our fuel demonstration flight, I had flown a 3 hour and 51-minute flight from Provo to our home base in SoCal. On that flight, I had run the left tank dry. So, I had the fuel truck put 1.5 gallons in the left tank and top off the right. We would take off on the right tank, level off, head for the practice area, and switch to the left tank to run it dry.

After a little bit, the fuel level in the left tank indicated zero and I hit the cancel button to shut off the red warning light. In my plane, about 5+ minutes later, the fuel stops flowing. If you have an engine monitor with fuel level and warnings, make a note of the time between when it hits zero, and when the fuel stops flowing. It will help you know when to really start watching that fuel pressure.

I told my friend we would keep an eye on the fuel pressure which was sitting at 4.1 psi. The first indication that it is about empty is an up and down fluctuation in the fuel pressure and the fuel flow. This is because it will start to suck a little air, which causes the fuel pressure to drop. Then it gets a little fuel again, which causes the fuel flow to momentarily increase as the pressure comes back up.

If you switch at that point, nothing happens, and you continue on your merry way. I wanted to show her the steady drop in fuel pressure, which is the real tell, so we continued flying on the now almost empty tank. I told her we were looking for that steady drop. I wanted her to see it wasn’t instantaneous from the 4.1 to zero. After a few moments, it started the steady drop. If you count down “9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4,” that is about the speed the fuel pressure goes from 4.0 to 3.9 to 3.8 to 3.7, etc. If you are paying attention, you have 15-20 seconds from the time it starts dropping to make the switch. The engine will never stumble, and nobody in the plane will know what transpired.

I reached down, switched to the right tank, and had her watch where the fuel flow momentarily jumped higher than normal before the fuel pressure stabilized and settled back down. The reason that occurs in a carbureted plane is because the bowl, which had been depleted when the fuel stopped flowing, was refilling. Once that occurs, the flow will go back down to normal levels.

There have been three instances when, although I was expecting it to run out when the red light started blinking, I got distracted and didn’t notice the fuel pressure dropping. When the engine quit, it had my full immediate attention. On one of those occasions, my wife was with me on the way back from Arizona and it grasped her complete and undivided attention, too! There was some apologizing that took place.

I also wanted my friend to see the engine stumble and stop, so I switched back to the left tank. We watched as the fuel pressure started dropping again, but this time I didn’t switch tanks. The pressure reached zero, the engine stumbled, and then it was very quiet, with the prop still windmilling. You need three things for the engine to run: fuel, air, and spark. With the propeller windmilling, there is air and spark, so all you have to do is reintroduce fuel to the equation. I quickly switched back to the right tank, and within a couple of seconds, the engine was running again.

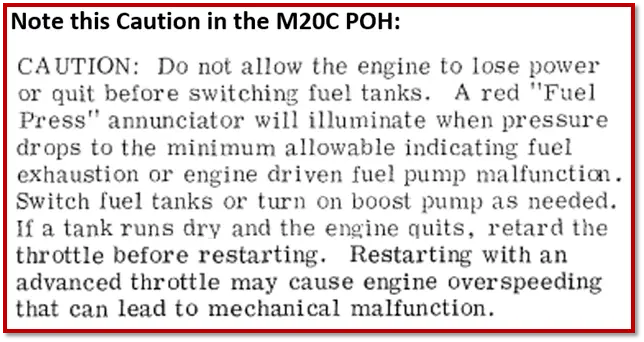

It is important to note that if the engine stops, you do not want to be at wide open throttle when switching tanks. That is because you could potentially overspeed the engine. Before switching tanks, you want to retard the throttle some.

After demonstrating what happens when the tank “runs dry,” her response was, “That’s it?”

“Yep,” I said.

“Thanks for taking the mystery out of it for me,” she replied.

I’ve lost track of the number of times I’ve run a tank dry. When it’s a 3-hour flight, generally I start on a tank, switch over, and then on descent I’m back to the fullest tank so I am landing with 10+ gallons of fuel in it. If it’s anything over about a 3 ½ hour flight, I’m running a tank dry.

Again, this is the experience with a carbureted engine. I have never done it in an injected engine, but what I have been told is, that while my engine will stumble when the pressure drops to zero, (courtesy of a little fuel left in the carb bowl), the injected engine will quit! It can also end up with air in the lines to the injectors, making a restart take a little longer than it would in the carbureted birds.

A Few Things to Keep in Mind

Speaking of air in the lines, it can cause some excitement on your next flight. I had run a tank dry going to Phoenix Mesa Gateway (KIWA) in Arizona a few years back. On the return flight, I started on the tank I had landed on, flew an hour and switched tanks. I always watch the engine monitor when switching tanks and was alarmed to see my fuel pressure begin to drop, along with the fuel flow. When something goes wrong, you undo the last thing you did, so I switched back.

My mind was running in overdrive, wondering what was wrong, and what could cause the pressure to start dropping. Obviously, it wasn’t getting fuel after I switched to what I knew was a full tank. I was considering if I should start looking for an alternate or turn back to where I started. KIWA was only an hour behind me, and I had 1 ½ hours of fuel remaining in the tank I was using. It dawned on me that I probably had air in the feed line from when the tank had run dry on the previous flight. With that in mind, I switched back again. The pressure dropped a little more, and then the fuel flow jumped up high. The pressure stabilized, and the flow came back to the normal range.

Another good thing to know is that if you have an engine monitor that alarms when you have low fuel levels, it is going to continue to alert you for the remainder of your flight. Yes, you have 15 gallons in the tank you are flying on, but it sees the zero in the other tank and will continue to remind you about it.

If you don’t already know, the senders are in the rear of the tank, inboard by the fuselage. If you are in a climb, they will show more fuel than what is there; in a descent, they will show less fuel. They are accurate in level flight. Don’t be alarmed if you showed 15 gallons when you started your descent, but a few minutes into it, you are only showing around 12 gallons. Those three gallons didn’t disappear. The fuel just moved toward the front of the tank.

Arguments Against Running a Tank Dry

I have read and heard the arguments against having an empty tank. Here are some of them and my response.

1) If you have an empty tank, your plane will be unbalanced, and you will have flight issues. It may be different if you have larger tanks, but in my plane that holds 26 per side, I notice no balance issues even on my recent flight with 24 gallons one side and nothing on the other.

2) What if all your fuel is in the right tank and you are flying right turns in the pattern? It could un-port and you stall out near the ground. First, if you are making a coordinated turn, there will be no issue at all. With 10 gallons in the tank, I’m not sure you could put it into an aggressive enough slip to un-port. However, if you have mismanaged your fuel and approach so poorly that you find yourself on final in a forward slip, with a few gallons left, hopefully you have enough bandwidth left to remember to slip the correct direction to force the remaining fuel against the fuselage.

3) If you run the tank dry it will pick up gunk left in the bottom of the tank. First, the pickup is raised above the bottom of the tank, specifically so it won’t pick up debris from the bottom. Second, you’ve been flying for hours with the fuel sloshing and bouncing around. Whatever debris is in the tank is likely already floating around and getting sucked up and caught in the filter at the gascolator.

4) What happens if your tank runs dry and when you go to switch back, the selector doesn’t work, or something goes wrong with the tank or lines from the tank you just switched back to? That would be a bad day. But why would the tank and feed lines that had been working perfectly a few hours before suddenly stop working? Highly unlikely. Why would the selector stop working? Also, highly unlikely. I will admit that I have a concern about something jamming the selector and I run my finger inside the cup it sits in every time to be sure nothing has fallen in there. Twice in my 950 hours, I have found a tiny pebble that must have fallen off the bottom of my boots. Maybe it would have caused a problem, and maybe not. I’ll never know because I check each time.

None of this is to try and change anyone’s Standard Operating Procedure or encourage them to do something that would make them feel uncomfortable. I am not a CFI and it has been many years since I slept in a Holiday Inn. There are many more experienced Mooney pilots than myself. This article only gives my experience running tanks dry and why I do it. Again, I stress that this is the experience in a carbureted plane. For those with injected planes, I am told that the pressure will steadily drop the same way. If you catch it before zero, the engine never stops, and it’s a non-event. If you let it stop in your injected bird, the restart will be a little different.

If you have run a tank dry, I would love to hear your experience. Or, if you think I’m crazy for doing so, feel free to blow up my inbox. 😊